A unique collaboration between the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics (MEAM) at Penn Engineering and the Morris Arboretum & Gardens is harnessing innovation to resurrect a piece of Penn and Philadelphia history: Springfield Mills.

Dating back to 1761, the mill sits on the Wissahickon Creek—which originally powered the mill by water—and offers a compelling glimpse into the agricultural and engineering landscape of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.

Springfield Mills stands out as the most complete inventory of original gristmill works and related machinery in the area, with only four remaining mills in the Wissahickon. The three-and-a-half-story mill served multiple functions, including sawing timber, grinding corn into flour, and pumping water for field irrigation.

THE MILL’S LEGACY AND RESTORATION

In the early 2000s, the Run-of-the-Mill volunteers—a dedicated group including engineers and employees of the Morris—worked to restore the mill back to functionality.

The volunteers and staff developed a public tour and handled all necessary maintenance, allowing the Morris to host demonstration days, giving visitors an immersive experience with the century-old machinery that allowed the millers to grind grain and corn to flour. When running, the mill hums with the steady sounds of shaking sieves, grain elevators, the rumbling of gears, and the grinding of millstones. “When you see it and what it captures, you’re like, ‘This is the most incredible thing ever,'” explains Bryan Thompson-Nowak, director of education at the Morris.

These demonstrations go beyond mere mechanical display. “Obviously, the physics of it is captivating, but the message we want to get across is that the flour you get doesn’t magically appear,” Thompson-Nowak says. “We try to make this a full experience.”

THE CHALLENGE

The mill had relied on a 5-horsepower electric motor added approximately 20 years ago, which drove the machinery through a belt-drive system. This approach caused significant wear on the mill’s wooden components, particularly the lignum vitae bearings—a super-dense wood used in the original construction. Two years ago, the volunteers noticed the belt shuddering and jumping and deemed it unsafe to run.

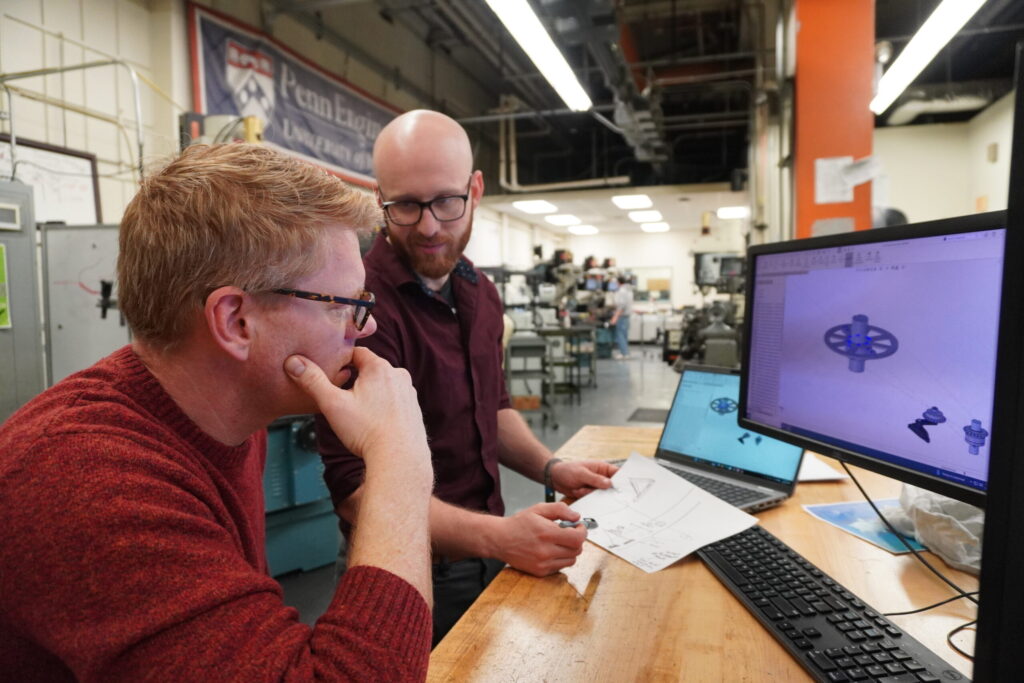

After reading an article on the Makerspaces at Penn, Thompson-Nowak emailed two technical staff in MEAM: Jason Pastor, senior coordinator of instructional labs, and Ari Bortman, educational laboratory coordinator, asking whether they would be interested in taking a look at the mill.

Once on-site, Pastor and Bortman could see the damage right away. “The belt was pulled so tight you could pluck it like a guitar string,” says Pastor. The extensive tension ruined the bearings on the top and bottom, as they were not designed for such radial load.

THE SOLUTION

Before the belt system was added, the mill ran using the great gear, a 6-foot diameter, 1-foot thick wooden gear that powers the smaller gears throughout the building. “One of the volunteers, Ted Bell, suggested we move the power back to the great gear,” explains Pastor. To do this, Pastor and Bortman manufactured a two-foot diameter sprocket and chain, which will eliminate load on the auxiliary shaft that the rubber belt had driven. “The great gear is so wide because that gives it a big lever,” Pastor explains. “It doesn’t have to be super strong to turn these smaller gears because it has a big mechanical advantage.”

This approach offers several benefits, as Bortman notes: “We don’t need to put in a new motor or electrically rewire everything. This would require less tension to prevent slipping and would allow us to use the motor and gearbox already in place in the mill.”

The solution requires sophisticated fabrication work, including:

- CNC mill and lathe work for precision components in MEAM’s Precision Manufacturing Lab;

- waterjet cutting at Pennovation Works to reduce the sprocket weight by over 25 pounds;

- and a custom aluminum collar design to support the sprocket.

This split-component design facilitates installation around existing machinery. “It’s really cool to work on something at this big a scale,” reflects Bortman. “A lot of stuff for researchers is small and precise, and this ended up being big and also very precise.”

LOOKING FORWARD

When the project is complete, the Morris hopes to resume public demonstration days. In addition, Pastor, Bortman, and Thompson-Nowak highlight how great it has been to connect with each other and collaborate. “It’s getting people thinking about working together and people know now that we’re able to help,” says Pastor.

This article was written by Claire Sibley for the Morris Arborteum & Garden’s Seasons Spring/Summer 2025 magazine. You can view the full issue here.