This article was written by Nathi Magubane for Penn Today.

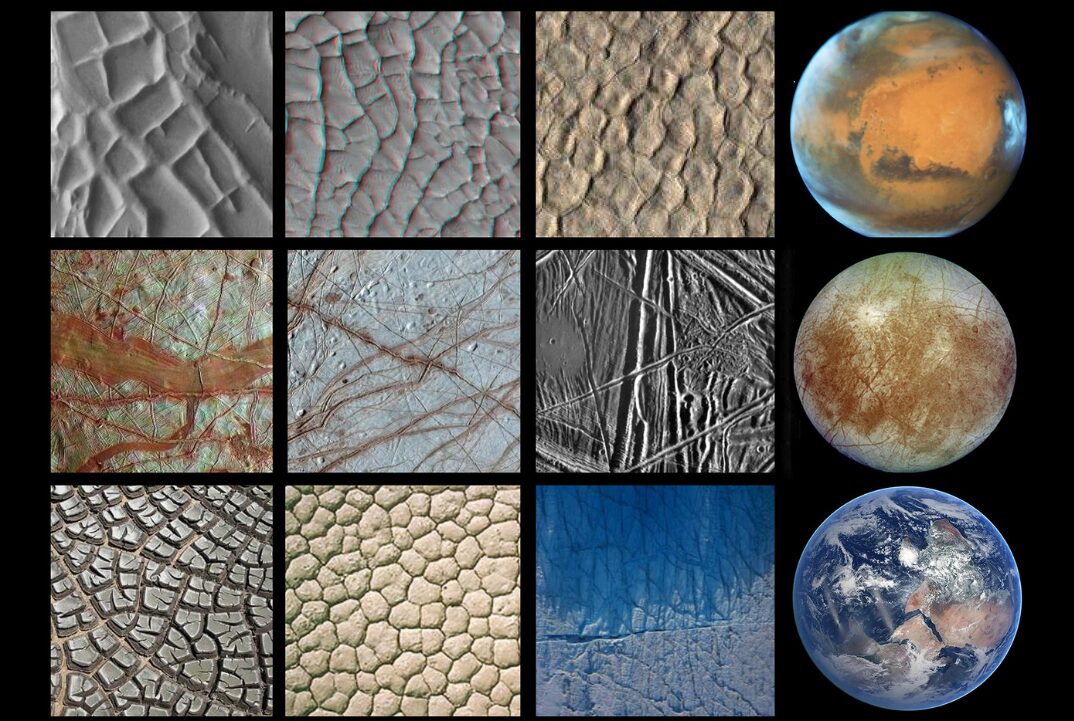

When a mudflat crumbles on Earth, or an ice sheet splinters on one of Jupiter’s moons (Europa), or an ancient lakebed breaks on Mars, do these fractures follow a hidden geometric script? Could similar patterns on another planet hint that water once existed there—and possibly sustained life?

To most, these questions would be idle curiosities, but to geophysicist Douglas Jerolmack at the University of Pennsylvania and mathematician Gábor Domokos at Budapest University of Technology and Economics, they hold the key to decoding the surfaces of distant planets across the solar system.

Their latest study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, suggests that the way a planetary body fractures is no random accident, and their findings could offer insights into detecting potentially habitable environments on other worlds.

“What’s wild is that nature keeps favoring the same patterns across vastly different environments,” says Jerolmack, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Endowed Term Professor of Earth and Environmental Science. “We expected some consistency, but the degree to which planetary surfaces organize themselves into predictable crack geometries—whether it’s ice, rock, or mud—was surprising. It suggests these patterns are fundamental, not just quirks of specific planets.”

Their insights build upon prior work where the team confirmed a prediction by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato who once declared that Earth itself was composed of cubelike units. In that paper, they demonstrated that, “rather surprisingly, if you take the thousands of fragments that are produced and you measure the number, you count the number of faces and corners and edges, and you average the hell out of it,” Jerolmack says, “then you end up with six as an average for the faces, eight, as an average number for the vertices, and 12 for the number of edges.”

Their more recent work, however, focuses on two-dimensional fracture networks on planetary surfaces, examining the patterns of cracks on thin shells of planetary bodies, rather than the shapes of individual fragments.

“We wanted to explain patterns on other planets that are here right now, because the problem is, we don’t get to see how they evolved,” says Domokos. “We weren’t there. And we can’t go back in time.”

The challenge, he explains, is that they are working with a single frame of a moving picture—a frozen snapshot of the current state of crack patterns on planetary surfaces. The forces that created these networks are no longer directly observable, and the fractures may still be evolving toward some unknown future state.

“But what if, from this one snapshot, you could extrapolate the whole plot of the movie?” Domokos asks.

To read the full article, click here.