Red blood cells, long thought to be passive bystanders in the formation of blood clots, actually play an active role in helping clots contract, according to a new study from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania.

“This discovery reshapes how we understand one of the body’s most vital processes,” says Rustem Litvinov, a senior researcher at the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM) and co-author of the study. “It also opens the door to new strategies for studying and potentially treating clotting disorders that cause either excessive bleeding or dangerous clots, like those seen in strokes.”

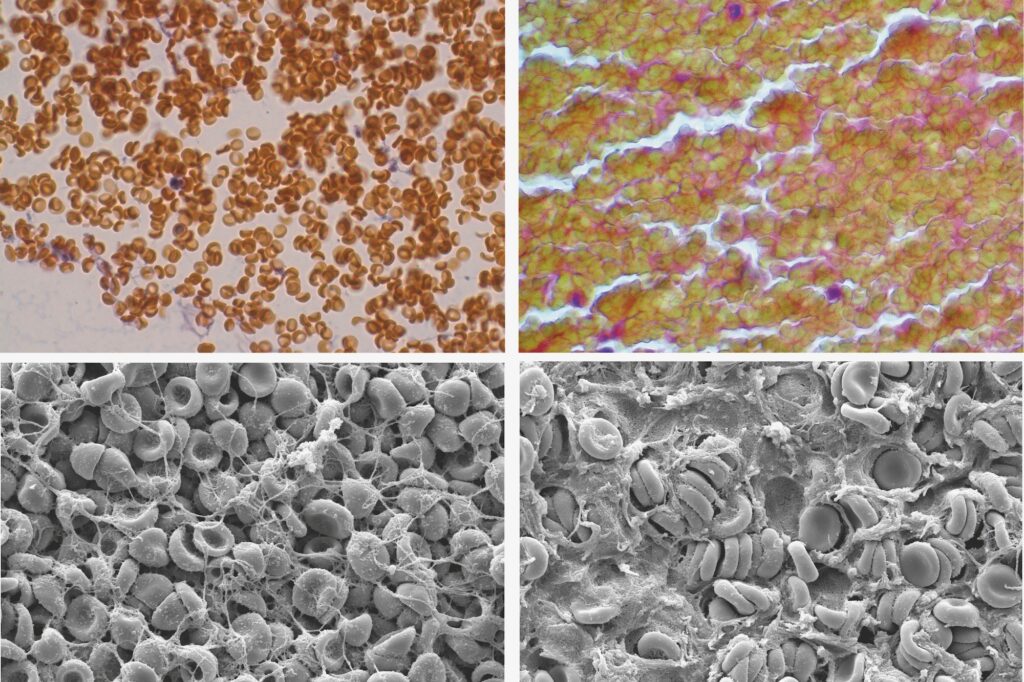

The finding, published in Blood Advances, upends the long-standing idea that only platelets, the small cell fragments that initially plug wounds, drive clot contraction. Instead, the Penn team found that red blood cells themselves contribute to this crucial process of shrinking and stabilizing blood clots.

“Red blood cells have been studied since the 17th century,” says co-author Prashant Purohit, Professor in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics within Penn Engineering. “The surprising fact is that we’re still finding out new things about them in the 21st century.”

An Unexpected Finding

Until now, researchers believed that only platelets were responsible for clot contraction. These tiny cell fragments pull on rope-like strands of the protein fibrin to tighten and stabilize clots.

“Red blood cells were thought to be passive bystanders,” says co-author John Weisel, Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology within PSOM and an affiliate of the Bioengineering graduate group within Penn Engineering. “We thought they were just helping the clot to make a better seal.”

That assumption began to unravel when Weisel and Litvinov ran a test they expected to fail. They created blood clots without platelets. “We expected nothing to happen,” says Weisel. “Instead, the clots shrank by more than 20%.”

To double-check their results, the team repeated the experiment using regular blood treated with chemicals to block platelet activity. The clots still contracted. “That’s when we realized red blood cells must be doing more than just taking up space,” says Litvinov.